There’s nothing like the warm, comforting touch of nostalgia to smooth life’s rough edges and temper worries about the future, at least for a little while. Likened to a powerful drug by novelist Kate Christensen, nostalgia has long been a drug of choice for restaurant designers and developers — and for good reason. Whether expressed overtly or subtly, nostalgic cues have the power to help carry a narrative and create transportive experiences for guests.

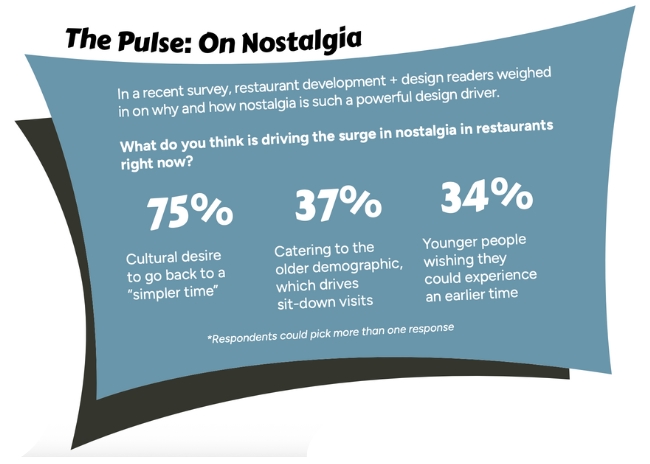

Transportive to where? To a “simpler time,” according to three in four respondents to a recent rd+d The Pulse survey that asked readers why they believe nostalgia is a big driver in restaurants right now. For some, that might mean transportive to pre-digital times, pre-COVID-19 times, times associated with adolescence or childhood, or times romanticized and experienced vicariously through TV and movies.

Whatever the draw, designers agree that nostalgia plays an integral part in effective restaurant design.

As part of a renovation at the Thompson Central Park hotel, Burger Joint relocated to a new, larger space. Image courtesy of John Pearson

As part of a renovation at the Thompson Central Park hotel, Burger Joint relocated to a new, larger space. Image courtesy of John Pearson

“We’re definitely seeing a stronger focus on nostalgia today. People crave familiarity and want something they can latch onto or experience that may not really exist or predominate anymore, such as a particular style,” says Lance Saunders, associate at Philadelphia-based Stokes Design & Architecture. “And on some levels, it’s kind of bleak times right now. Restaurants that offer nostalgic references provide some respite, not unlike movies do.”

For Saunders, designing restaurants is akin to designing movie sets — putting the pieces in place to help tell a story. “People like looking back but also tend to conflate nostalgia with what they absorb from pop culture more so even than from their own specific personal memories,” he says. “It’s about visual storytelling of movies, in particular, and how production designers curate sets so well that the effects bleed into people’s lives and memories, and they crave the feeling they get from watching the movie. It makes an emotional connection. We all want to be the hero of our own stories, and that kind of mixes up in our brains and turns to this craving for nostalgia. Whether overtly or more subtly, restaurant designs that draw on nostalgia can create similar types of connections.”

Driven by nostalgia for the restaurant’s time-worn, gritty ambience, Celano Design dismantled and relocated many of its organically collected design elements to maintain Burger Joint's original vibe in the new space. Image courtesy of John Pearson

Driven by nostalgia for the restaurant’s time-worn, gritty ambience, Celano Design dismantled and relocated many of its organically collected design elements to maintain Burger Joint's original vibe in the new space. Image courtesy of John Pearson

Restaurants, after all, aren’t simply places to eat. Especially where table service is offered, they’re touchy, feely, sensory, happiness-inducing places uniquely poised to bring past and present together via food, music, ambience, aromas, graphics, materials, color and furnishings. Indeed, entire nostalgia-rich concepts — originals and modern versions — continue to thrive and attract customers for the experiences they offer, from listening bars, speakeasys and classic diners to fish camps, pizza parlors, supper clubs and classic steakhouses.

Michael Poris, founding partner at McIntosh Poris Architects in Detroit, says nostalgia factors into virtually every restaurant project. In some cases, it’s quite literal, but more often than not, it’s layered and interwoven more subtly.

“I look at nostalgia in a bit of an abstract way,” Poris says. “It’s partly memory and history, but it goes deeper than that. To me, it’s like a collage. When you’re creating a collage, you conceive of something. It may not be obvious, but as [art critic and theorist] Rosalind Krauss suggests, there’s a buried origin — an original, foundational element. The person looking at it may not consciously realize it or see it, but it’s there. Two examples in art are Picasso and Mondrian. Whether it was a violin or a vase that Picasso was painting, he transformed it into something else, but the origin is still there. And with Mondrian, the grid isn’t just geometry. It’s abstracted from the buried origin of water, trees, the balance of nature. So, we think a lot about buried origin. How do we perceive something, whether it’s the actual history or something nostalgic, and then conceive and create something new but with that original element still buried within it? Maybe it’s as simple as including a certain color; maybe it’s a form. It’s hard to define and different on every project.”

Top Take: Verbatim

“Today’s guests crave experiences that feel intentional, layered and different from their everyday routines. Referencing a certain era, style or cultural memory is less about longing for the past and more about building a richer, story-driven environment that aligns with the food, beverage or entertainment concept. In many cases, these nostalgic cues act as a creative framework; they help define menu direction, shape immersive design choices and enhance an ‘eatertainment’ offering that feels cohesive and shareable. Ultimately, it’s not about replicating the past; it’s about using the past as raw material to craft a unique, future-forward experience that people can’t get anywhere else.”

— Anonymous reader survey respondent

Something Old, Something New

In some instances, the real estate sets the stage for conceptual nods to nostalgia. Older buildings with rich histories can provide built-in memories and nostalgic connection points with which to work.

When McIntosh Poris set out to design the Detroit Foundation Hotel and Apparatus Room restaurant, housed in a 100-year-old firehouse, the history of the building naturally informed the design approach. “It wasn’t necessarily nostalgia, per se, as much as 100 years of history, 100 years of firefighters who had worked there,” Poris says. “We didn’t want to make it all firehouse-centric. It’s subtle and more symbolic; it’s something new, but the history is clearly still there, so there is a pull of nostalgia. Everyone has some memories of a firehouse, whether from when they were a kid playing with fire trucks or through stories or movies.”

In Wilmington, Del., Stokes Architecture & Design was tasked with reimagining the look and feel of The Green Room, the signature 100-year-old restaurant at the Hotel Du Pont, now rebranded as Le Cavalier at The Green Room. It, too, is a textbook case of blending past and present, nostalgia and modernity through design.

“We inherited a beautiful, historic space with a lot of original finishes and details that we had to work with,” Saunders notes. “But the restaurant had become stuffy and tired — somewhere you might take your grandma on Mother’s Day, but with no appeal as an energetic spot for a night out. Our approach was to reference what was there — the oak paneling, brass chandeliers, gilded details, ornate ceiling, etc. — but not to replicate. We chose trim profiles that are more modern versus the old curlicue profiles, for example. We added a bar and center banquette seating to add energy, using cleaner, less ornamental lines and referential materials. Rather than pulling from the 1910s, when it was built, we pulled instead from the 1940s to ’60s, weaving in threads through the decades of design. The end result is a space that feels at once nostalgic and modern. It all blends together in a way that it wouldn’t have had we just tried to replicate.”

Finding that balance of old and new is the key to effectively incorporating nostalgia in design, Saunders adds. “You don’t want a space to feel stuck in a specific time period,” he cautions. “A layered approach with years of design woven into it can be much more effective. There’s a certain ease that it puts people at to think of a restaurant having been open for decades, a place worth being at versus something that’s extremely modern, new and stuck in one point of view.”

Rather than pull from the 1910s when the DuPont Hotel was built, Stokes’ design team pulled from the 1940s to ’60s, weaving in threads through decades of design. The historic hotel’s reimagined signature restaurant, Le Cavelier at The Green Room, now feels both nostalgic and modern. Image courtesy of Jason Varney

Rather than pull from the 1910s when the DuPont Hotel was built, Stokes’ design team pulled from the 1940s to ’60s, weaving in threads through decades of design. The historic hotel’s reimagined signature restaurant, Le Cavelier at The Green Room, now feels both nostalgic and modern. Image courtesy of Jason Varney

Even when a place is new and lacks built-in references to fond memories or simpler times, designers add warmth and familiar touchpoints, offering guests carefully curated hits of nostalgia. Vincent Celano, founder and CEO of New York City-based Celano Design Studio, says it can actually be more difficult in some ways to work with spaces already full of history and nostalgia. Such spaces, he suggests, can carry baggage that makes it difficult to fully express a new concept or design direction.

“When working in a new space, we can purchase, curate and create exactly the level of layers of nostalgia that we want,” Celano explains. “It might be distressed walls, or maybe a late-1800s bar that we’ve sourced and repurposed. Creating an installation of such elements that tell a story often has a better way of coming across ultimately as more authentic. That’s because every piece is curated, and how they all come together is very intentional, versus having to work hard to complement existing and historical elements.”

When the Parker New York hotel changed ownership to become Thompson Central Park, the luxury property underwent a full remodel. But its iconic restaurant Burger Joint, a graffiti-filled hole-in-the-wall tucked behind a big curtain off the lobby, lives on in a new, larger space. Celano and his team handled the design, which was entirely driven by nostalgia for Burger Joint’s original form — a small, lines-out-the-door place beloved by locals and tourists alike for more than two decades.

“As part of the renovation, we had to move Burger Joint into a new space,” Celano says. “This was a case where preserving the historical and nostalgic elements was critical. We literally had to dismantle so many elements of the old space — the posters, stickers and celebrity signatures on the walls, which had collected organically over the years — and move them to the newer, bigger space. It was challenging and very fun to take a fresh, new space and at the same time maintain the authenticity and nostalgic vibe that existed in the original. We just let loose. The whole studio came in to help graffiti the walls.”

New concepts, too, can come to life and enable emotional connections with guests through skillful balance of old and new. When McIntosh Poris and Dallas-based Coeval Studios together set the stage for

Gilly’s Clubhouse, a 3,700-square-foot modern sports bar in Detroit, childhood memories of sports and the owners’ wish to honor their late son helped the designers infuse the space with nostalgic references.

“It’s definitely a fancy new sports bar, but layered with the modern and new — the buried origin — is nostalgia for the client’s son, Nick Gilbert,” Poris says. “His nickname was Gilly, and he was developing this sports bar with his dad, but passed away before it was finished. So the whole place is sort of nostalgic for him and for his excitement around sports from childhood on. There’s even a little arcade in it because Nick really wanted some arcade games. And there are shelves of sports paraphernalia that he collected as a kid. A lot of the design elements capture a kid’s excitement around sports, and that resonates with most anyone who’s ever been a kid or has fond memories of watching sports.”

While modern and new, Gilly’s Clubhouse in Detroit draws on nostalgia to tell a story and create an emotional connection. Honoring the client’s late son, the designers sought to capture childhood excitement around sports, incorporating memorabilia collections and other elements that resonate with sports fans of any age. Image courtesy of John D’Angelo

While modern and new, Gilly’s Clubhouse in Detroit draws on nostalgia to tell a story and create an emotional connection. Honoring the client’s late son, the designers sought to capture childhood excitement around sports, incorporating memorabilia collections and other elements that resonate with sports fans of any age. Image courtesy of John D’Angelo

Meanwhile, at Bombshell Treat Bar in Berkely, a Detroit suburb, McIntosh Poris sought to evoke an old-school corner candy or ice cream shop, but one with fresh and modern twists. The 2,200-square-foot storefront features a bright white backdrop, against which candy-colored design elements, including sprinkle-patterned walls, cherry-red banquettes and awnings, and a large exterior mural, pop.

“It’s designed to feel like something you might remember from — or just imagine from — your childhood,” Poris says. “The layout, the colors, the branding all trigger some of that memory, but it’s still very unique and new with its own identity versus trying to be just a knockoff from another era.”

Of course, as with any powerful drug, designers caution that moderation is key, as is judicious editing of nostalgic references. Go overboard or try to be too literal in the design approach, and the risk of creating what feels like imitation — a space without its own unique narrative and authenticity — runs high.

“We never want to just ‘Epcot Center’ something,” Saunders notes. “And the best way to avoid doing that is to really lean into history and research to figure out the means and methods of why something that is authentic — something from a particular time period or pop-culture reference — was that way. What made it beautiful? What made it work? What materials did they have at the time that then seemed modern or necessary to use? We start with that, but then layer into the design things that have happened since, including more modern aesthetics. If it’s well-researched and done thoughtfully, then those nostalgic elements really work and resonate with a wide variety of guests — not just those with a fondness for a particular period or memory.”