Ask anyone who has opened a restaurant to describe their experience with the permitting process, and responses will vary from “piece of cake” to “nightmarish.” The former, however, are the unicorns — rare and a little bit magical. After all, the sheer number of permits required, the maze of state and local agencies that are typically involved, shortages and turnover in inspection and review staffing, and quirky variances by municipality can lead to a supersize portion of frustration, delays and extra costs.

Securing permits for Yogi Gogi, a Korean BBQ concept in Washington, D.C., that features down-draft burners at each table, required extra ventilation and fire suppression, including sprinklers over each table. Image courtesy of //3877

Securing permits for Yogi Gogi, a Korean BBQ concept in Washington, D.C., that features down-draft burners at each table, required extra ventilation and fire suppression, including sprinklers over each table. Image courtesy of //3877

Invest in Relationships

David Shotwell, construction manager for franchisee Flynn Restaurant Group, which operates more than 1,200 Applebee’s, Arby’s, Panera Bread and Taco Bell units, says the secret ingredient for getting permitting done as quickly and smoothly as possible is relationships. To that end,

he tries to meet and share information with city managers and/or economic development staff very early in the process.

“During our due diligence, we’ll often sit down with the city and do a walk-through of the whole process,” Shotwell says. “It’s a sort of courtesy review with representatives from each city department present. It gives us a chance to say, ‘This is what we’re proposing, what we plan to do.’ It’s pretty broad, and you get more comments once drawings are done, but it gets things started, lets them flag certain things they’ll be looking for, and helps establish relationships that are important later on in the process.”

For every project, Shotwell also insists on hiring an architect or permit expediter with extensive experience in the local market. “If the architect has done a lot of work in that city, they can usually handle it,” he notes. “But I’ve found over the years that it really comes down to having someone on your side who has strong relationships established locally. Even if you have to pay extra to bring an expediter in, it’s worth it. They know how the local officials work and how they like things to be handled. If you don’t know that or don’t follow it, things get frustrating for everyone.”

John Gardner, president of Wallace Consulting & Construction Inc. in Highland, Md., also emphasizes the importance of local expertise and nurturing relationships early in the permitting process. Gardner, whose firm provides lease review and negation, construction management and general construction services, says it’s important first of all to make sure you’re talking to the right officials, particularly in large urban markets that may have multiple jurisdictions. In the D.C. market, he points out, businesses on opposite sides of the street in some areas cross a county line and have completely different inspection and permitting offices.

In some municipalities, local architectural review boards, historic and environmental preservation boards and/or neighborhood councils may also be involved, adding more layers to the process that are important to know about from the start.

“Some locations definitely have more red tape,” says Eddie Navarrette, chief consultant at Los Angeles-based FE Design & Consulting, which steers restaurant clients through the permitting process. “In this market, for instance, special California Coastal Commission permits are required for businesses going into coastal areas. Those requirements are different from those of the local municipality. If you don’t know that, you can be halfway through the process before you find out that while the city said you need 10 parking stalls and you based your plans on that, the Coastal Commission says you need 20. Some urban neighborhoods also have more regulation than others, especially where there’s a lot of public input and push-back against density, noise, traffic and/or alcohol service.”

Gardner’s best advice: Figure out the space you’re going to take or the specific area you’re considering and then do careful homework. “Start talking to local officials,” he says. “And reach out not just to the regulatory offices and appropriate boards and commissions but to the Department of Commerce and/or economic development officials as well. Get them excited about your concept and what you’re planning to bring to the market. Make inroads with folks who can help you politically push the process if you get stuck somewhere later on.”

Washington, D.C.-based architecture and design studio //3877 handles the permitting process for many clients both locally and nationally. David Tracz, founding partner, says relationship building and thorough information gathering are first critical steps, followed by developing clear, easy-to-read plans that give officials exactly what they want in the format in which they want it.

“Whenever we get started on a project, we’re making those calls right away to try to understand things like length of review times and to gather basic information about what they want to see and what they’re really focused on in that jurisdiction,” Tracz says. “Step two is then to make sure that all of the local code requirements are very clearly addressed in the first couple of sheets of plan drawings. We try to show them right up front that we know and have addressed exactly what the current zoning is, what the fire ratings are — all of the things that the code officials are going to be looking for. We closely follow their requested formats, and in some cases, we’ve gone to the point of using different-colored drawings to help delineate occupancy and things like that so it’s easier to read. And we usually have someone in our office who’s not involved in the project review the drawings just to be sure they’re clear before we go in for review.”

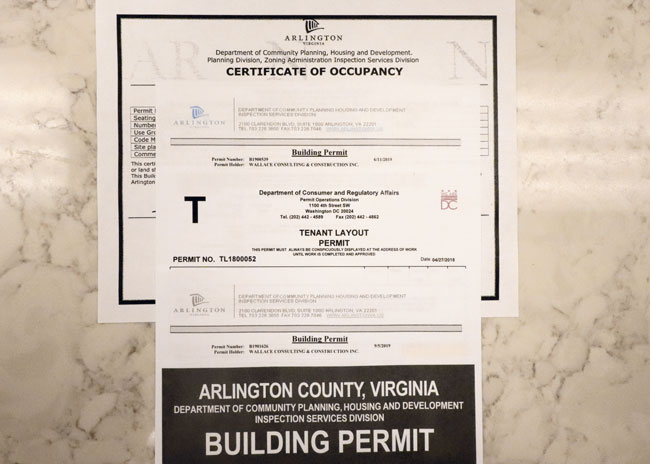

Highlighting the need to know local requirements early on is the fact that, some jurisdictions mandate that Certificates of Occupancy be applied for separately and can take several weeks to be approved. Image courtesy of Wallace Consulting & Construction

Highlighting the need to know local requirements early on is the fact that, some jurisdictions mandate that Certificates of Occupancy be applied for separately and can take several weeks to be approved. Image courtesy of Wallace Consulting & Construction

Do the Homework

While the knee-jerk reaction is often to blame red tape and bureaucratic inefficiency for permitting delays, Gardner adds that operators are often their own worst enemies. Inexperience and unrealistic expectations combined with lack of due diligence are typically the culprits.

In particular, Gardner says, inexperienced restaurateurs or those going into new markets often fail to research intricacies of local codes. “Most jurisdictions work off the International Building Code (IBC) system, which is revised every few years by the International Code Council,” he says. “But local jurisdictions decide which sections to adopt and when. One might be working off the latest IBC codes from 2018, while another could still be working off of those from 2012 or 2014. And some smaller markets don’t even use the IBC code. One rural Texas market that we were working in uses the Southern Building Code. If you don’t know that early, or if you just bring your architect in from another state and present plans based on the more common IBC requirements, they’ll be rejected, and you’ll have to start over.”

And requirements for things like sprinkler systems can vary considerably. Shotwell notes that locations under 10,000 square feet in some cities aren’t required to have sprinkler systems installed. In other cities, “even if you have only 2,500 square feet, they’ll make you put a sprinkler in even though the building might not be fire rated,” he says. “If you’re in Fairfax, Va., for instance, there’s a 90-day waiting period, to get a sprinkler inspection, or a $10,000 fee to have an emergency inspection done. Neither of those options is attractive when you’re on a tight budget and just trying to get the doors open.”

Indeed, too many operators also sign leases before they fully understand potential limitations of a space, Gardner adds. That often leads to permitting delays and unanticipated associated costs.

Navarrette agrees, cautioning clients to always have a clear view of a location’s infrastructure before signing on the dotted line. “Exhaust, plumbing, electricity, grease interceptor — these things take time to investigate properly, and a lot of operators just don’t do sufficient due diligence. Aside from the zoning, aside from going to the city planner or the building department to talk about code requirements and timing, you need to personally know the logistics of construction,” he says. “How is this really going to work? Can we pull this off in this location in a way that the city will approve? How would we install a grease interceptor? Is there going to be enough power for a restaurant here? If not, what is that process going to look like, what’s it going to cost, what does it mean for the schedule and who’s going to pay for it? When you’re going into a lease and you have a good understanding of all this, you can negotiate with the landlord and save a lot of money if upgrades are required to meet your own needs and current code requirements.”

Timing, Navarrette adds, very much depends on type of location and how the permitting process will impact the ability to do what’s needed to get the doors open. His general estimate for the L.A. market: at least six months before construction can begin and another six months to complete the build-out.

One additional aspect of the process that surprises a lot of operators in terms of timing, Garner notes, concerns Certificate of Occupancy (CofO). “In most jurisdictions, when the work is complete, you receive a final building inspection, pay a small fee and receive your CofO,” he says. “But in some jurisdictions, you need to apply for it, and it can take weeks or months to be approved. Typically, contractors and architects exclude the CofO process from their scope of work as it’s part of the permitting and licensing process. So, if you’re new to business and don’t have a construction manager or permit expediter working with you, you could be 100% finished and ready to open but not able to get a CofO for several weeks.”

Consider Pay to Play

To be sure, the traditional permitting process earns its reputation in many municipalities for being cumbersome, frustrating and less than customer friendly. But some changes are afoot that are easing the pain.

One that’s taking hold and improving efficiency is the transition from paper applications submitted at multiple physical offices to digital submissions. Another, particularly where budget cuts have hampered city inspection staff’s ability to keep pace, is to turn the inspection and review process over to third-party firms.

Still another, available now in many larger markets, is an “express” option, which can take the review and permitting approval process down from weeks or months to just days.

Washington, D.C., for instance, in 2018 introduced an optional fast-track plan review and approval process that can be done in just a day.“You pay an additional fee, but you can meet with permit officials for one or two meetings and walk out with a permit,” Tracz says. “Even with things going digital and submitting drawings and applications online, the back-and-forth of getting reviews, comments, responses and approvals takes a lot of time. If you don’t understand what they’re asking, you might answer it wrong, and that sets you back. The express process is great because you’re sitting across the table from those who reviewed your drawings. They give you their comments and questions, and you can explain and clarify right there, bypassing the usual back and forth.”

Shotwell is a big fan of such expedited permit review procedures, too. He feels the additional fees charged, which are typically based on size of project, are a relatively small price to pay for the time saved.“In Minneapolis, for instance, we can now get an express review and permit approval in just 48 hours,” he says. “We might be paying $5,000 or more for it, but seriously, that’s about one day’s sales. We get a permit in two days and can break ground the following Monday. Compare that to having to pay rent for several weeks while waiting to go through the traditional process, and you quickly see it’s not an additional expense. It’s a huge savings.”