Adaptive reuse projects breathe new life into old, vacant buildings — but they’re not for the faint of heart.

Brome Burgers & Shakes was once a jewelry store. Photo by Oliver NasralahWhen signing on to develop Ophelia’s, his newest operation on the fringe of downtown Denver, chef Justin Cucci didn’t really have the time or money to do another restaurant. He already had two successful spots — Root Down and Linger — operating at full throttle. But when local developer Paul Tamborello purchased the historic Airedale building and approached Cucci with the opportunity to help bring the abandoned, Victorian-era structure back to life, the offer was too tempting to pass up.

Brome Burgers & Shakes was once a jewelry store. Photo by Oliver NasralahWhen signing on to develop Ophelia’s, his newest operation on the fringe of downtown Denver, chef Justin Cucci didn’t really have the time or money to do another restaurant. He already had two successful spots — Root Down and Linger — operating at full throttle. But when local developer Paul Tamborello purchased the historic Airedale building and approached Cucci with the opportunity to help bring the abandoned, Victorian-era structure back to life, the offer was too tempting to pass up.

Although the building was in a state of decay, Cucci, whose first two restaurants reside in a former gas station and a mortuary also owned by Tamborello, saw a chance to marry creative concept development with adaptive reuse in a way that would honor the building’s past. The fact that its past included a brothel, a peep-show venue and, most recently, an adult book and video store just added to the appeal for Cucci. Working with architecture and design firm BOSS Architecture, he created an eclectic, boudoir-inspired concept that boldly celebrates the building’s past lives.

Original brick walls were retained, where possible, including one in the main dining room that now carries an image of Ophelia, the concept’s namesake and muse.Opened in April as a 425-seat “gastro-brothel” and live music venue on the main and lower levels of the four-story building (the upper two floors now house a hip, upscale hostel), Ophelia’s illustrates the extreme highs and lows of adaptive reuse projects. Lengthy, costly, exhilarating at times and exasperating at others, it’s an example of adaptive reuse at its best, ultimately sustaining and preserving buildings that still have good bones while reinventing and reinvigorating them for new use.

Original brick walls were retained, where possible, including one in the main dining room that now carries an image of Ophelia, the concept’s namesake and muse.Opened in April as a 425-seat “gastro-brothel” and live music venue on the main and lower levels of the four-story building (the upper two floors now house a hip, upscale hostel), Ophelia’s illustrates the extreme highs and lows of adaptive reuse projects. Lengthy, costly, exhilarating at times and exasperating at others, it’s an example of adaptive reuse at its best, ultimately sustaining and preserving buildings that still have good bones while reinventing and reinvigorating them for new use.

Interest in significant adaptive reuse is on the rise, with a combination of economic, environmental, urban renewal and historic preservation motives driving this trend. It’s not for the faint of heart, and most such projects promise twists and turns that add time and money. But proponents say they can also promise character and authenticity that consumers love and that simply can’t be manufactured into new-build projects, making them more than worth the trouble.

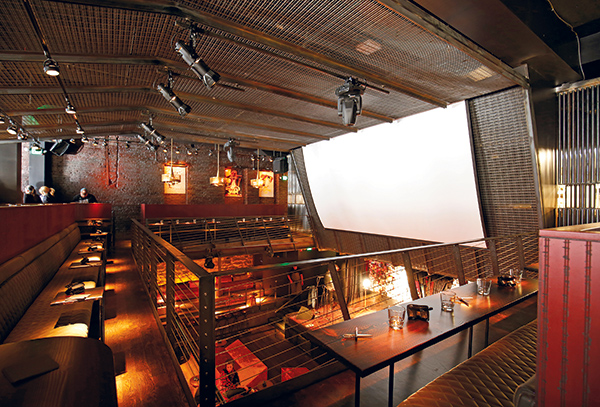

Dilapidated and crumbling when the project began, the Airedale building’s two lower levels have been reborn as Ophelia’s, with a main floor that includes a bar, lounge and restaurant seating overlooking the music venue below. Chuck Taylor, director of operations at Chicago-based Englewood Construction, says his company has seen adaptive reuse projects on the rise and that opportunities for restaurants have been particularly strong as landlords struggle to fill vacant spaces. “We’ve run into a lot of projects that were multiuse spaces in urban environments, for instance, where developers took an old office building or warehouse and converted it to apartments or condos but left the ground floor open for retail. Landlords have found, however, that making those retail deals has gotten harder, so they’re turning to restaurants, which have been much more active. We do see restaurant groups or individual operators going after old vacant banks or firehouses just because they’re unique and it’s a cool idea, but the bulk of adaptive reuse projects seem to be initiated by landlords looking to fill spaces and being willing to make the investment to adapt them.”

Dilapidated and crumbling when the project began, the Airedale building’s two lower levels have been reborn as Ophelia’s, with a main floor that includes a bar, lounge and restaurant seating overlooking the music venue below. Chuck Taylor, director of operations at Chicago-based Englewood Construction, says his company has seen adaptive reuse projects on the rise and that opportunities for restaurants have been particularly strong as landlords struggle to fill vacant spaces. “We’ve run into a lot of projects that were multiuse spaces in urban environments, for instance, where developers took an old office building or warehouse and converted it to apartments or condos but left the ground floor open for retail. Landlords have found, however, that making those retail deals has gotten harder, so they’re turning to restaurants, which have been much more active. We do see restaurant groups or individual operators going after old vacant banks or firehouses just because they’re unique and it’s a cool idea, but the bulk of adaptive reuse projects seem to be initiated by landlords looking to fill spaces and being willing to make the investment to adapt them.”

Such was the case for Cucci, whose Ophelia’s is the marquee — but not the only — Airedale building tenant and who didn’t have to assume the entire risk or cost of repairing and repurposing the building.

Such was the case for Cucci, whose Ophelia’s is the marquee — but not the only — Airedale building tenant and who didn’t have to assume the entire risk or cost of repairing and repurposing the building.

“I’d worked with Paul on my other two restaurants, both of which were adaptive reuse projects,” Cucci says. “He knows I love buildings with a history and that I try to fit my restaurants into their history rather than cover it up. When he bought the Airedale he called me and asked if I’d do a restaurant there. I fell in love with the building and its story, even though it was dilapidated. I loved the idea that here’s this beautiful National Historic Register Victorian building with such a sordid past. It had good bones, and Paul was willing to put a lot of the money into the infrastructure to bring it up to code. He handled the core and shell of the building, and then we came in and did our own core and shell and finish for our space.”

Investigate Infrastructure

Denver’s historic Airedale building, once home to a brothel, peep shows and an adult bookstore, now houses chef Justin Cucci’s restaurant and music venue, Ophelia’s. Cucci used the building’s colorful history as the springboard for the concept, which celebrates sensuality. Photos by Adam LarkeyTaylor notes that infrastructure — or lack thereof — typically becomes the biggest killer of adaptive reuse projects for restaurants and that failure to do proper due diligence can prove very costly. An old building may exude charm and exciting design possibilities, but without adequate water supply, sufficient waste lines, ductwork, ventilation, grease interceptors, and so on, it can quickly turn something that looked like a gem on the surface into a giant and costly headache.

Denver’s historic Airedale building, once home to a brothel, peep shows and an adult bookstore, now houses chef Justin Cucci’s restaurant and music venue, Ophelia’s. Cucci used the building’s colorful history as the springboard for the concept, which celebrates sensuality. Photos by Adam LarkeyTaylor notes that infrastructure — or lack thereof — typically becomes the biggest killer of adaptive reuse projects for restaurants and that failure to do proper due diligence can prove very costly. An old building may exude charm and exciting design possibilities, but without adequate water supply, sufficient waste lines, ductwork, ventilation, grease interceptors, and so on, it can quickly turn something that looked like a gem on the surface into a giant and costly headache.

Investigating occupancy codes becomes essential too, Taylor says. “In a lot of adaptive reuse situations, you’re not only changing the use but you’re changing occupancy, and that’s a completely different set of codes. Sometimes, for example, it means you’re also adding a very expensive sprinkler system to a facility just by changing how it will be used.”

As part of the adaptive reuse project, Ophelia’s lower level, originally little more than a dirt-floored crawl space, was excavated several feet deeper to allow for installation of a stage and dance floor. A large hole was cut from the center of the main floor to integrate the two levels. Photo by Adam LarkeyMany times, these types of issues aren’t fully investigated up front, nor is an agreement reached in the lease deal as to who will be responsible for funding the updates, Taylor adds. “Is it the landlord or the tenant? If it ends up being the tenant, those things can quickly turn an operator’s pro forma upside down,” he cautions. “We’ve had a number of deals that ultimately don’t get done because of the expense of adding the infrastructure necessary for a restaurant. You really need to know all of this and bring in the right engineers and others who can advise you before you sign anything.”

As part of the adaptive reuse project, Ophelia’s lower level, originally little more than a dirt-floored crawl space, was excavated several feet deeper to allow for installation of a stage and dance floor. A large hole was cut from the center of the main floor to integrate the two levels. Photo by Adam LarkeyMany times, these types of issues aren’t fully investigated up front, nor is an agreement reached in the lease deal as to who will be responsible for funding the updates, Taylor adds. “Is it the landlord or the tenant? If it ends up being the tenant, those things can quickly turn an operator’s pro forma upside down,” he cautions. “We’ve had a number of deals that ultimately don’t get done because of the expense of adding the infrastructure necessary for a restaurant. You really need to know all of this and bring in the right engineers and others who can advise you before you sign anything.”

Despite the fact that he’d done two adaptive reuse projects already, Ophelia’s proved to Cucci that there’s always more to learn in this regard.

A corner building constructed as a jewelry store in the mid-1900s is now home to Brome Burgers & Shakes, Sam Abbas’ fast-casual, organic, grass-fed burger concept. The 3,700-square-foot space was transformed into an open, contemporary, light-filled restaurant in 120 days.“Now that the project is done, I know there were a lot of things that I just didn’t have enough experience with to ask questions about and that ultimately ended up on my bill,” he admits. “It’s really important to do your due diligence and to have clear agreements with your landlord up front. And it’s tough because in adaptive reuse projects there are constantly things coming up that you just didn’t think about. Things like, ‘Oh yeah, we need railings around the HVAC units on the top floor. Who’s paying for that?’ It usually ends up being the tenant.”

A corner building constructed as a jewelry store in the mid-1900s is now home to Brome Burgers & Shakes, Sam Abbas’ fast-casual, organic, grass-fed burger concept. The 3,700-square-foot space was transformed into an open, contemporary, light-filled restaurant in 120 days.“Now that the project is done, I know there were a lot of things that I just didn’t have enough experience with to ask questions about and that ultimately ended up on my bill,” he admits. “It’s really important to do your due diligence and to have clear agreements with your landlord up front. And it’s tough because in adaptive reuse projects there are constantly things coming up that you just didn’t think about. Things like, ‘Oh yeah, we need railings around the HVAC units on the top floor. Who’s paying for that?’ It usually ends up being the tenant.”

All told, Cucci says, the Ophelia’s project came in around 20 percent higher than he’d initially budgeted, in part due to costs he didn’t realize he’d be responsible for and in part due to design changes that came up as the project evolved.

All told, Cucci says, the Ophelia’s project came in around 20 percent higher than he’d initially budgeted, in part due to costs he didn’t realize he’d be responsible for and in part due to design changes that came up as the project evolved.

Restaurant companies with strong financials and a track record of success might be willing to make the type of investment needed to adapt an attractive location for restaurant use, says Craig Pryde, AIA, LEED AP at KTGY, which has offices in Illinois, Virginia, Colorado and California. But Pryde cautions smaller operations against biting off more than they may be prepared to chew. At a minimum, he says, operators should go into adaptive reuse lease discussions with eyes wide open. If they’re to be responsible for the cost of updates to the building, they should also be prepared to drive a favorable rent situation that allows them to recoup the capital investment and stay afloat, he says.

Among the happy discoveries during demolition of the jewelry store were 15-foot ceilings, cedar plank roof decking and original concrete floors, all of which were incorporated into the restaurant’s interior design. Photos by Oliver NasralahPryde adds that beyond basic infrastructure issues, adaptive reuse sites should also be carefully evaluated for things like signage codes, restrictions on altering facades, and investment that may be required to bring them up to ADA compliance.

Among the happy discoveries during demolition of the jewelry store were 15-foot ceilings, cedar plank roof decking and original concrete floors, all of which were incorporated into the restaurant’s interior design. Photos by Oliver NasralahPryde adds that beyond basic infrastructure issues, adaptive reuse sites should also be carefully evaluated for things like signage codes, restrictions on altering facades, and investment that may be required to bring them up to ADA compliance.

“When you think about the fabric of buildings for adaptive reuse, our accessibility guidelines are relatively new,” he says. “Many were built before accessibility standards were a factor, and many were built for private industrial or other business use. It’s common to find sites where you have to go up three or four steps from the sidewalk to enter the building, for instance. That immediately becomes an issue if you want to open a restaurant, because you’re changing the use of the building to public access.”

Expect the Unexpected

Regardless of how thorough the initial due diligence, adaptive reuse veterans say surprises are inevitable. Sometimes, they’re happy surprises (like uncovering beautiful craftsmanship or original materials that can be incorporated into your design), and sometimes they’re not (such as damage or structural hurdles that just can’t be assessed until the project team begins peeling back the building’s layers).

Sam Abbas launched his new fast-casual Brome Burgers & Shakes last fall in a building that was originally a jewelry store in downtown Dearborn, Mich. He experienced both types of surprises. Abbas, who also owns the four-unit Yogurtopia franchise in Dearborn, purchased the vacant corner store and convinced the city to lease a portion of a public park/walkway space adjacent to it for an outdoor patio.

“I thought it would be a simple project, like some of my other locations where you just go in and take things down to studs or cinder blocks and start from scratch or finish off a shell in a new building. Turns out it wasn’t so simple,” Abbas says.

Among the happy discoveries when the original finishes began to come down were high ceilings and beautiful cedar plank roof decking. “Right away, the design started to transform because we originally thought we’d have standard 10-foot ceilings, and now we find cedar trusses 15 feet off the ground. That gave us something great to work with as a design feature,” notes Oliver Nasralah of the Hallarsan Group, who worked with Abbas on concept development, architecture, design and branding. “We also uncovered original concrete floors under the carpeting, which we were able to grind smooth

and polish.”

Some of the less pleasant discoveries stemmed from the building’s original life as a jewelry store. A large safe in the front of the building proved difficult to extract. All of the display cases and security systems were still in place. And walls and ceilings were burglar-proofed to an extreme.

“The amount of steel and concrete that had to come down was crazy,” Nasralah says. “When we first looked at the space, I thought, ‘OK, some drywall work, maybe some two-by-fours up there, no big deal.’ But it was all suspended in so much steel and so many rods. The original demo bid was for about 4 dumpsters, but they ended up using 15 or 20 to get it all out of there. We also discovered thin wires stapled in the ceiling across the rows between the trusses as part of the security system. If someone tried to enter through the roof and severed one of them, the alarms would go off. We actually tried to keep as much of that in as possible to speak to the history of the building, but it was a challenge that we didn’t anticipate having to work around.”

BOSS Architecture’s Kevin Stephenson, who worked with Cucci on Ophelia’s and has done several other adaptive reuse projects, notes that in some instances — particularly for sites listed in the National Register of Historic Places — restrictions limit what the design team can do. At Ophelia’s, he and Cucci wanted to expose old timber in the main section of the restaurant and an old wall of dilapidated plaster and paint. “We weren’t able to leave the timber exposed, but instead we ended up salvaging a lot of floor joints and things like that that came out of a big hole we cut in the floor that overlooks the basement music stage,” Stephenson says. “We had it re-milled and built a bar out of it. We also ended up having to replaster a wall that we would have rather left exposed because the historic preservation folks said that was more honest to what it was originally rather than what it had become. That can be a challenge in some projects because you’re working with restrictions or entities that have a different point of view.”

Historic restrictions or not, part of the fun of adaptive reuse projects is discovering just what’s under the surface of older buildings and figuring out what can be reused or repurposed. Ideally, Stephenson contends, the objective is always to incorporate and retain the original character of the building while infusing it with new life.

“It’s always a process to discover what you should retain and what you shouldn’t retain,” he says. “What’s old and dirty and a bad thing, and what’s old and dirty and a good thing? That’s subjective. And what original materials can you retain that will pass safety inspections? There are a lot of things working against you, such as the need for fire proofing and other code requirements. But that’s all part of the unique challenge of adaptive reuse projects. It’s not apples to apples compared to new construction, but that’s also part of their beauty.”

Voices of Experience: Tips for Adaptive Reuse

“Have patience when working with old buildings, and make sure to work with an experienced contractor who’s careful and who goes step by step to bring it back to life.” — Kevin Stephenson, BOSS Architecture

“There’s no such thing as too much due diligence, and insisting on clear, up-front lease negotiations to determine who pays for what is critical.” — Justin Cucci, Ophelia’s

“If you’re going to do adaptive reuse, do it with celebrating the building’s history in mind. Find out what makes it unique and what place it had in the community; don’t just cover up what it used to be.” — Stephenson

“You’re absolutely going to find stuff that has to be addressed that you didn’t think of or plan for. Make sure you have a good contingency both for time and budget.” — Cucci

“If you’re going into an older space, try to go into one that’s already been cleaned out and is ready for new construction.”

— Chuck Taylor, Englewood Construction

“Think mechanicals. Is there adequate basement/ceiling/roof space to put mechanical equipment and exhaust distribution? A lot of new equipment will need to fit into the existing envelope, and it will need to be easily accessed to keep maintenance costs down.” — Craig Pryde, KTGY

“Minimize surprises by using 3-D modeling. It helps to ensure that everything is built exactly as it’s designed to be.”

— Oliver Nasralah, The Hallarsan Group

“Don’t let anyone tell you it’s impossible. Ask questions, tap outside experts for input, break it down and simplify to see if it’s really impossible or just something that they haven’t done before.” — Sam Abbas, Brome Burgers & Shakes